Abstract

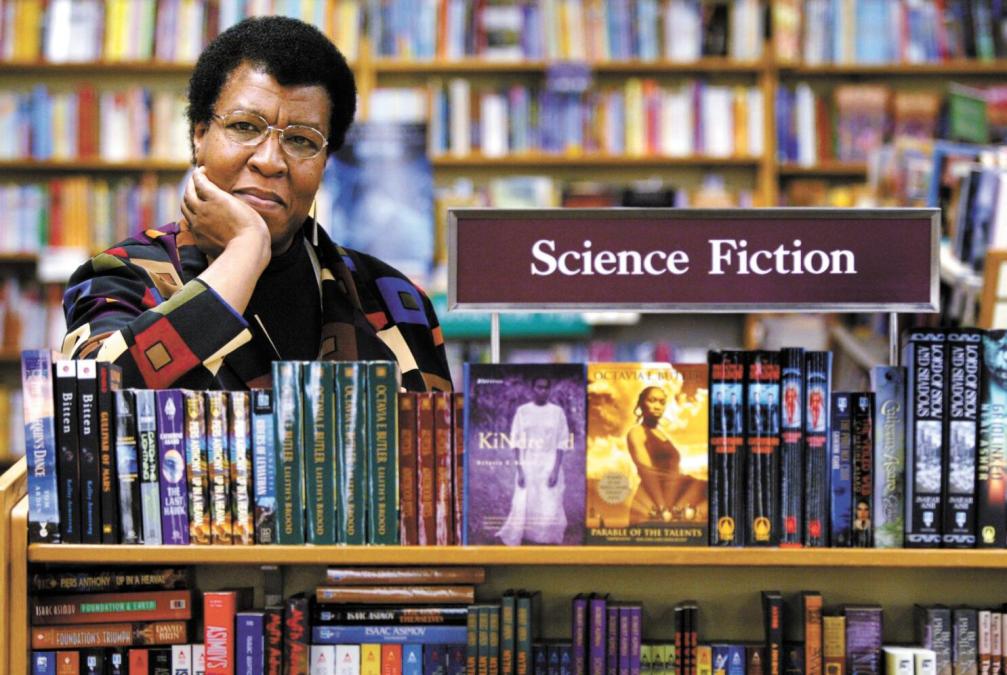

There are several themes that reoccur throughout the genre of sci-fi and particularly dystopian fiction. One of these themes is the presence of capitalism in the dystopian world. In several pieces of fiction in this genre, capitalism is extrapolated to its extreme, exemplifying the real world’s economic policies and how they would affect a society when brought to their farthest level. We see in these works how as neoliberal economics leads corporations to become the main source of power within society, they become the de-facto governing faculty while government transforms into an almost passive body that serves only the purposes of maintaining order that serves the interests of these massive corporations. While this is a theme present throughout the genre, I will focus particularly on Octavia Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower.. Butler’s novel shows a world where neoliberal economics have begun a societal death spiral leading to a dystopic future.

Neoliberal Economics as a Corrosive Force

All dystopian fiction is rooted in the troubles of the society the work is written in. In some sense all portrayals of society depicted in this genre contain some amount of commentary on the real-world conditions that are present at the time of the work’s creation. Considering this we should understand that few factors affect our real-world society more than economic policy. Thus, one important aspect to consider in the worlds presented in these fictions is their representations of economy and government.

Considering this, it is easy to see why Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower has become so well regarded in the realm of dystopian fiction. It’s depiction of a near-future has been called prophetic by many reviewers (Leo) for the way it extrapolates modern day American politics and social conditions to their logical extremes. The story revolves around a girl named Lauren Olamina who lives in a walled village named Robledo in what remains of the United States after years of internal turmoil. The world Butler has crafted for us is one where social order has fallen apart. Rampant violence and discord has taken over most of the country, and in many ways Lauren’s position, while not enviable by most modern standards today, is a privileged one in the world she inhabits. However, the protection of the walls is not iron-clad. Several times in the story these walls are breached, whether it be by the “street poor” outside or stray bullets. (Butler, 50) Despite this moderate level of protection Lauren’s village is eventually destroyed and most of her family and friends killed in the process, where she must then begin a long journey on foot with two other characters in an attempt to survive.

In the early passages of Parable of the Sower we get glimpses at the ways that America has become the dystopian setting Butler has penned. The first glimpse comes when Lauren’s narration tells us that “Dad says water now costs several times as much as gasoline. But, except for arsonists and the rich, most people have given up buying gasoline.” (Butler, 18) This quick line explains to us how the market present in the world of the novel has affected the ability for people to acquire the necessities for life. The rise in the price of water can only be due to its commodification. It has been viewed not as a necessity for life, something that should be valued and preserved for distribution to as many as possible or at the very least subsidized, but a commodity to be sold for the highest price one is willing to pay. This is an astute understanding of the real world today, as there is a lucrative market in betting on future water scarcity according to Michael Lewis’ The Big Short. Lauren’s narration speaks more about the privatization and corporatization rampant in her society as the chapter continues

“Donner has already said that as soon as possible after his inauguration next year, he’ll begin to dismantle the ‘wasteful, pointless, unnecessary’ moon and Mars programs. Near space programs dealing with communications and experimentation will be privatized—sold off. Also, Donner has a plan for putting people back to work. he hopes to get laws changed, suspend ‘overly restrictive’ minimum wage, environmental, and worker protection laws for those employers willing to take on homeless employees and provide them with training and adequate room and board. What’s adequate, I wonder? A house or apartment? A room? A bed in a shared room? A barracks bed? Space on a floor? Space on the ground? And what about people with big families? Won’t they be seen as bad investments? Won’t it make much more sense for companies to hire single people, childless couples, or, at most, people with only one or two kids? I wonder. And what about those suspended laws? Will it be legal to poison, mutilate, or infect people —as long as you provide them with food, water, and space to die?”

(Butler, 27)

This section of narration gives us an thorough overview of how neoliberal economics has been implemented in the world of Parable of the Sower in a general sense. We see the ways that space exploration, a program that historically has always been a federally funded entity organized towards scientific and national initiatives is now considered wasteful and those parts that are considered worthy of keeping are being privatized. Again, we see some real-life parallels here with the current day privatization of space programs with companies such as Space-X and Blue Origin. Another real-life parallel comes in the form of political and cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s comments on the rise of privatization in his book “Capitalist Realism.” He says,

“It is worth recalling that what is currently called realistic was itself once ‘impossible’: the slew of privatizations that took place since the 1980s would have been unthinkable only a decade earlier, and the current political-economic landscape (with unions in abeyance, utilities and railways denationalized) could scarcely have been imagined in 1975.”

(Fisher, 17)

Fisher here is referring to the trend of privatization that began in the 1980s in America and continues more voraciously to this day. The novel extends this even farther as characters have to pay a fee for emergency services such as fire and police. (Butler, 32) Continuing this same trend of a world catered to corporate entities, we see the suspension of laws that protect workers and the environment with the intent of “putting people back to work.” This proposition is an in-book version of trickle-down economics, an economic system that was created with the idea that if the company makes more money it will inevitably “trickle down” in the form of wages. However, this idea doesn’t really take the human propensity for greed into account, and we see this in the passage. When Lauren begins to question just how little will be given to these employees now that these protection laws have been stripped away, she is concerned because she understands that those that run these companies will want to maximize their profits by any means possible, which includes depriving their employees of basic necessities. This all becomes even more shocking when we consider that the novel tells us that the currency has become incredibly inflated and that a thousand dollars is barely enough to feed someone for two weeks. (Butler, 312) The strongest line in the entire passage is when Lauren says “And what about people with big families? Won’t they be seen as bad investments?” The classification of families as “investments” perfectly sums up the commodification of the human being within the world that Butler has created in the novel. As far as corporations in the book are concerned, human beings serve only the purpose of labor (investment) or liability (debt). Parable of the Sower’s world is one wherein everything is commodified.

This commodification of the human body extends beyond the level of corporations into the realm of sexuality and gender. In the world of the novel prostitution and sexual slavery run rampant, and it’s for this reason that Lauren decides to travel as a man. Clara Escoda Agustí speak on this in her essay “The Relationship Between Community and Subjectivity in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower” saying,

“…Butler dramatizes and overcomes the exploitation of the female that ensues from such a form of capitalism. In her novel, sexual slavery and prostitution are inherent tendencies of a system that favors profit at the expense of human well-being.”

(Agustí, 351)

Mention of women having to sell their bodies to survive is sprinkled in throughout the book. In chapter 11 Lauren talks about how she believes her brother Keith who goes outside Robledo’s walls and seems to come up with money for their mother without giving an explanation is likely involved with crime and prostitution. Later on in chapter 15 she speaks about how when walking on the freeway they see prostitutes and desperate peddlers of food or water along the road trying to either sell themselves or thieve to survive. We see in these segments not just the human body as a commodity, but sexuality as a commodity.

Another critical element of how neoliberal politics has been extrapolated in Parable of the Sower is the presence of company towns. In chapter 11 the reader learns that there is a company town opening up near Robledo named Olivar, created by one of the mega-corporations that hold de-facto control over the United States, KSF. We hear about these towns through more of Lauren’s narration:

“Room and board. The offered salaries were so low that if Dad and Cory both worked, they wouldn’t earn as much as Dad is earning now with the college. And out of it they’d have to pay rent as well as the usual expenses. In fact, when you add everything up, it’s clear that with the six of us, they couldn’t earn enough to meet expenses….Anyone KSF hired would have a hard time living on the salary offered. In not very much time, I think the new hires would be in debt to the company. That’s an old company-town trick—get people into debt, hang on to them, and work them harder. Debt slavery. That might work in Christopher Donner’s America. Labor laws, state and federal, are not what they once were.”

(Butler, 120-121)

Here Lauren explains to the reader exactly how these company towns function. They lure desperate people in through the prospect of employment and housing, with the caveat of having to pay rent to the company for said housing. The salaries the companies pay will never meet the cost of living and thus the workers are always indebted to the company and become literal slaves to the organization. Gregory J. Hampton draws a parallel between this system and sharecropping in his essay, “Migration and the Capital of the Body: Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower,” saying,

“The community members are forced into trading their freedom for protection from hostile urban forces. The salaries offered by the KSF would eventually force any and all of its laborers into debt slavery, much like sharecropping did in the rural south during the Reconstruction era…Thus, both Lauren and her father understand that if Olivar succeeds, more privatized cities will be established. Like a virus the KSF will divide America into sources of cheap labor and cheap land for the sole purpose of profit.”

(Hampton, 65)

We see this idea Hampton puts forward of the company cities spreading like a virus in the novel, as we see Lauren respond to dialogue asking if there will be more privatized cities, “Bound to be if Olivar succeeds. This country is going to be parceled out as a source of cheap labor and cheap land.” (Butler, 129) The reason that Lauren believes there will be more privatized cities is that, given the chaos of the world they are living in, they provide a security that those that are truly desperate will flock to. In a way these company towns can represent a kind of utopia, representing a reprieve from the chaos of the outer world, but for the reader looking at them from a type of detached lens we understand them to be anything but.

This idea of company towns may seems a far stretch of the imagination by today’s standards, but there is some precedent for the idea even in the modern zeitgeist. A 2014 op-ed from The Guardian entitled “Google has sleep pods, Yelp has beer—why don’t we just live at work?” proposes the idea of people living at their offices. Granted, the article speaks about the luxurious offices of tech giants such as Google and Facebook, however the idea of being housed by your employer is still there. In fact, one section of the article says,

“It’s only natural I suppose. As the industrial age, at least for us in the west, puffs its last climate-punishing puff, we can throw off the yoke of the commuter and choose to work where we live, or live where we work. Just as we did in those fondly remembered days when we were all serfs.”

(Moran)

While the idea of this can be seen as hyperbolic by today’s standards, the allusion to serfdom does bring to mind a certain comparison to the company towns presented by Octavia Butler in her novel.

Social Despotism

The societal and economic hardships that those living in the world of Parable of the Sower face have larger effects than creating financial difficulty. The world Butler has penned is marked by constant violence, distrust and tribulation. Even in the early sections of the novel where much of the story is taking place within the walls of Robledo we are still exposed to the violence outside. The first instance is when a young child, Amy, is shot by a stray bullet and killed through the gate of the village. Butler leaves the reader with the looming sense of chaos just outside the walls until Lauren must go out and face it for herself. In these early segments of the book we notice the psychological effect that this has on the characters. They crave for the past, for a time not so violent and where they did not have to struggle so hard to simply survive. We see in the adults of the Robledo a nostalgia, hoping for a past before the corporatizing of America and before the subsistence living that they are now subject to. There is a shared sense among this older generation that if they simply wait things out long enough and retain hope it might one day return. Paula Guerrero speaks on this in her essay “Post-Apocalyptic Memory Sites: Damaged Space, Nostalgia, and Refuge in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower.” She says,

“For the older generation, home is a fantasy from the past that ought to be kept, and nostalgia is the means to maintain it, to preserve hope that this past will one day return. Their nostalgia is, in the words of Svetlana Boym, ‘restorative,’ aimed at rebuilding ‘a home that no longer exists.’”

(Guerrero, 29)

We see this demonstrated in the novel during a conversation between Cory and Lauren. Cory, Lauren’s stepmother, pines for the times when the city lights would brighten the darkness that comes with nightfall, while Lauren disagrees with her, appreciating the natural beauty of the stars. Here we see the difference in the generational ideas of what they hope for. Cory hopes for a return to the former economic prosperity that society used to have, while Lauren can only appreciate what little they have and cannot hope for more simply because this is the only life she has known. The older generation hopes for the past, and the younger generation simply cannot afford to hope. In many ways this makes Lauren more apt to survive in the adverse conditions of the America that Butler has presented us with. Her inability to feel nostalgia for this past allows her to be prepared for the future chaos to come. Jerry Phillips speaks about this in his essay “The Intuition of the Future: Utopia and Catastrophe in Octavia Butler’s ‘Parable of the Sower.’” He says,

“In contrast to the residents of Privatopia, who seek to avoid the realities of the world, Lauren genuinely transcends the “chaos” without, because she understands that only by working through the contradictions of the world does only move beyond them.”

(Phillips, 303

As the novel continues we see more of the destitute conditions of the country. People are constantly stealing from one another. Lauren and her traveling companions come across corpses on several occasions, sometimes mutilated or burned. Everything outside of their protective bubble of Robledo is a free-for-all, with everyone looking out for themselves. There is no sense of social cohesion. Lauren knows this well and it is this that accounts for her survivalist mindset. We see it on display in a piece of dialogue where she says, “Nothing is going to save us. If we don’t save ourselves, we’re dead.” (Butler, 59) And again when she says

“I am one of the street poor, now. Not as poor as some, but homeless, alone, full of books and ignorant of reality…there’s no one I can afford to trust. No one to back me up.”

(Butler, 156)

It seems that in this world the social breakdown has also extended to racial and gendered violence, as Lauren travels as a man for safety reasons. They speak about how rapes and sexual violence occurs often in unguarded areas. Laws are in place, they are simply not enforced and the police in the novel are privatized, working for fees. We see an example of this towards the end of the novel when police speak to Bankole regarding a fire on his sister’s property

“The deputies all but ignored Bankole’s story and his questions. They wrote nothing down, claimed to know nothing. They treated Bankole as though they doubted that he even had a sister or that he was who he said he was…They searched him and took the cash he was carrying. Fees for police services, they said.”

(Butler, 316)

They don’t investigate crimes, they are shown simply showing up where they are called, taking some notes, collecting their fees and taking their leave. The violence is not just against women but also has its roots in race as well. At one point the character Zahra, who is traveling with Lauren, says “Mixed couples catch hell whether people think they’re gay or straight. Harry’ll piss off all the blacks and you’ll piss off all the whites. Good luck.” (Butler, 171-172) What this implies is that a sort of racial tribalism has taken hold of the country. This makes the group that Lauren assembles by the end of the novel even more transgressive, as it represents both gender diversity and racial diversity.

Another significant social issue that the novel describes is that of the pyros (also occasionally called paints), a group of people that are addicted to a psychoactive drug that makes the users mesmerized by flames and start fires. These people are rampant throughout the country and pose a massive problem for the society. They are almost a Mad-Max like version of a drug addict gone mad in their own addiction. Butler describes them in the novel with the following,

“Crazies did that. Paints. They shave off all their hair. Even their eyebrows—and they paint their skin green or blue or red or yellow. They eat fire and kill rich people…They take that drug that makes them like to watch fires. Sometimes a camp fire or a trash fire or a house fire. Or sometimes they grab a rich guy and set him on fire…I heard some of them used to be rich kids, so I don’t know why they hate rich people so much. That drug is bad, though. Sometimes the paints like the fire so much they get too close to it. Then their friends don’t even help him. They just watch them burn. It’s like…I don’t know, it’s like they were fucking the fire, and like it was the best fuck they ever had.”

(Butler, 110-111)

In this description we see how tight of a grip this drug has on the populace. With how much of an effect we see the pyros having on the social stability in the country, we can imagine that, at least to some extent, this is a systemic issue. It is also notable here that the pyros seem to be disproportionately targeting the rich in their attacks. This frames their violence in another light. What the pyros do in the novel is undoubtedly brutal, however when we consider the idea that there may be some methodology or reason behind it, it dissuades the idea that the pyros are simply addicts that have lost control or a scattering of lost savages. They may be instead a group of people that have been neglected by the world, like many of the characters in this novel have, and lashed out in a more dramatic fashion. So we see this level of chaos and disorder not just in the form of theft, violence and rape, but also of hedonistic drug use, possibly caused by the systemic issues inherent in the world of the novel.

With all this social disorder also comes alienation from one another and a more general air of fear that can drive some such as the debt slaves to accept the status they are given. This is mentioned in the novel

“She decided then to run away, to take her daughter and brave the roads with their thieves, rapists, and cannibals. They had nothing for anyone to steal, and rape wasn’t something they could escape by remaining slaves. As for the cannibals…well, perhaps they were only fantasies—lies intended to frighten slaves into accepting their lot. ‘There are cannibals,’ I told her as we ate that night. ‘We’ve seen them.’

(Butler, 289)

Conditions like these can lead those who are living in the company towns as debt slaves to not look for other opportunities for life because it is too much of a safety risk to go out on your own. There is a tight and rigid power structure in place that reinforces the hierarchies of the society. All this social chaos and disorder in the world of Parable only serves to prop up these structures created by the exaggeration of neoliberal economic policies.

Conclusion

Octavia Butler’s novel serves as a harrowing look at how a future completely overtaken by neoliberal politics and privatization may look. Daniel Clausen was not too far off when describing the government in the novel as, “a logical ad absurdum version of small government ideology, having atrophied to the point where all that remains are taxes that seem to do nothing more than legitimize land ownership.” (Clausen, 274) Butler foresees a government beholden to the whims of massive corporations, curtailing of laws that protect workers and the environment, privatization of every service that can be privatized and ultimately debt slavery to employers. This inevitably leads to a world of widespread violence, social alienation and destitution across the country. It is a pessimistic look at America’s future.

The end of the novel contains seeds of hope, with Lauren’s ideology being steeped in the idea that small grass-roots organization can create something new for humanity. While she never intends to overthrow the prevailing powers that be, she works in small community-based movements. The tone at the end of the novel is best described as wary hopefulness, with this passage leaving us off towards the end.

“‘You know, as bad as things are, we haven’t even hit bottom yet. Starvation disease, drug damage, and mob rule have only begun. Federal, state, and local governments still exist—in name at least—and sometimes they manage to do something more than collect taxes and send in the military. And the money is still good. That amazes me. However much more you need of it to buy anything these days, it is still accepted. That may be a hopeful sign—or perhaps it’s only more evidence of what I said: We haven’t hit bottom yet.’ ‘Well, the group of us here doesn’t have to sink any lower.’”

(Butler, 328)